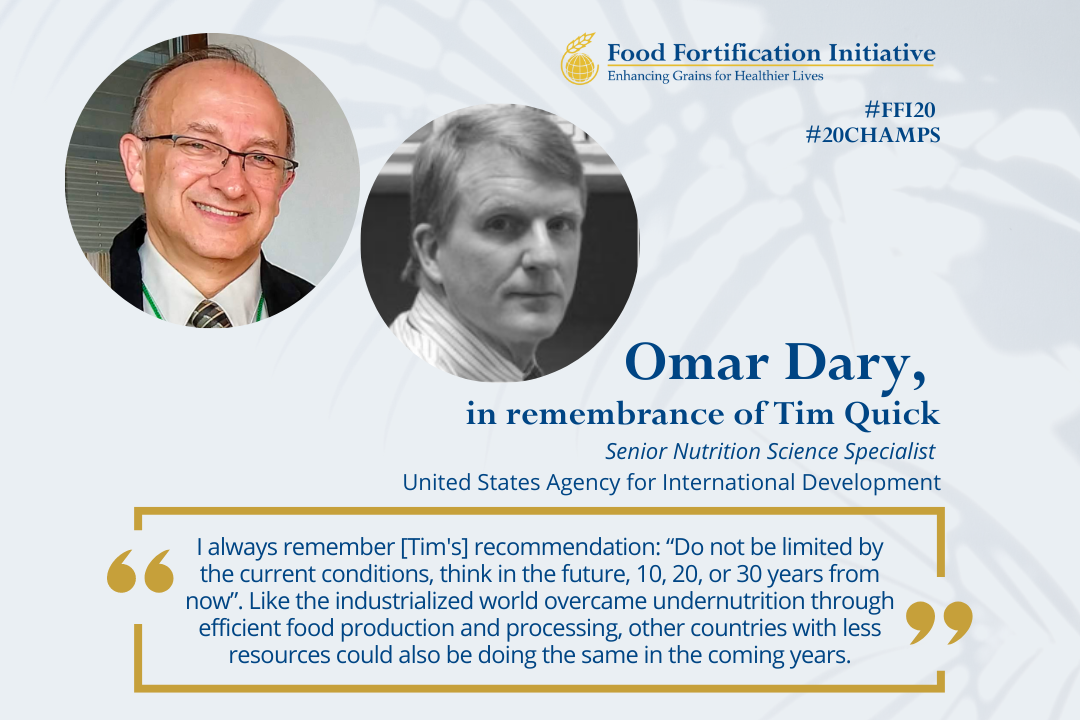

Senior Nutrition Science Specialist of United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

FFI: How did you become interested in nutrition?

Dary: When I came back to Guatemala in 1990 with a PhD in Biochemistry, I was lucky enough to find a position as a Nutritional Biochemist at the Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP). There, I inherited the food fortification programs that already had a history and legacy in Central American countries. Iodization of salt was introduced at the end of the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s, wheat flour fortification has been adopted by the industry since the 1960s, and sugar fortified with vitamin A was made possible through national programs in Costa Rica and Guatemala that began in the 1970s. My entry into the nutrition field was through food fortification programs as well as micronutrient surveillance in population surveys using biomarkers.

FFI: What inspired you to become involved with food fortification?

Dary: I inherited these programs as part of my job description at INCAP. There, I had the opportunity to contribute with the strengthening of the salt iodization programs in the Central American region, improve, and defend the existence of sugar fortified with vitamin A in Guatemala, and help for the extension of this program in Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. Later, I did the same thing for Zambia and Nigeria, and indirectly in Malawi, which are countries that are using sugar as a vehicle for vitamin A. In Central America, South America, East Africa, Jordan, and the West Bank and Gaza, I promoted the adoption of wheat flour fortification. I helped these countries change from fortifying with reduced iron to ferrous fumarate and include folic acid and other micronutrients that are not commonly added to this vehicle, such as vitamin B12 and zinc. In the East, Central, and Southern African region, I collaborated with programs to enact standards, train the public and the private sector, and introduce oil, maize, and wheat flour fortification in several countries. I participated in similar efforts in South America, Bangladesh, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. Some were successful, others not.

FFI: Could you describe Tim Quick’s achievements in the area of food fortification?

Dary: Tim worked for more than 25 years at USAID. He was always interested in micronutrients from promoting the development of methodologies to assessing biomarkers associated with micronutrient deficiencies. He supported the development of a method to determine the concentration of retinol binding protein as a surrogate for serum retinol. Tim also established productive relationships with the private sector. He supported large-scale food fortification (LSFF) and the use of targeted fortification in the manufacturing of products as complementary foods for small children as well as to improve the nutritional status of individuals affected by HIV. He was always interested in strengthening links with the private sector to improve their roles in public health nutrition. During the last months of his life, he was aware that his time was coming short to contribute more to public health nutrition. In response, he assumed the responsibility of collecting experiences and lessons learned from different institutions and professionals who have worked in food fortification during the last 30 years to produce the USAID Large-Scale Food Fortification Programming Guide and Results Framework, which we can consider as his eternal legacy in this subject. He was able to summarize the knowledge and practical applications of LSFF in public health nutrition. I am certain that these documents are going to guide the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of LSFF for many years to come.

[Editor’s note: Tim passed away on 25 July 2022.]

FFI: What do you think moved Tim Quick to do this?

Dary: Tim was convinced that, to improve the diets of many countries and societies, and consequently their nutritional and health status, the involvement of the private sector is essential. He advocated for increasing dietary diversity by promoting production and consumption of the food groups that are absent or insufficient in the diets of many vulnerable communities, as well as to improve the formulation of foods manufactured by industry to provide those nutrients that for any reason cannot be supplied in sufficient amounts by average daily diets. He acknowledged that, to cover the nutritional needs of all humankind—more than eight billion people now—we need to use all the resources that we have. Considering only natural foods is not realistic. Moreover, by combining natural foods with well designed and implemented food fortification programs, it will make it possible for people to establish balanced and affordable diets at low cost. I always remember his recommendation, “Do not be limited by the current conditions, think in the future: 10, 20, or 30 years from now.” Like the industrialized world overcame undernutrition through efficient food production and processing, other countries with less resources could also be doing the same in the coming years.

FFI: Now, going back your efforts in food fortification: How have you prioritized fortification in your work?

Dary: For me, LSFF is a practical, easy to implement, and low-cost intervention to complement the nutritional value of common diets when certain conditions are in place. These conditions are that a country has centralized food industries, that the cost of fortification can be added to the price of products, and that the public sector is able to maintain simple and low-cost enforcement and monitoring systems. LSFF is very flexible, and it can be adjusted to the different nutritional needs of every context. For example, it is important to add vitamin D to fortification standards in countries that do not often expose the skin to sunlight. It is important to add vitamin A, vitamin B2, vitamin B12, and zinc to fortification standards in countries with low supply of foods of animal origin. When LSFF is not possible, then other interventions, like biofortification and micronutrient supplementation, should be considered. Nevertheless, if the conditions are proper, experience has shown that LSFF is the most affordable and effective intervention to prevent micronutrient deficiencies.

FFI: What are the greatest challenges you have encountered in planning or implementing fortification programs? And how did you address those challenges?

Dary: LSFF has improved the nutritional and health status of billions of people. However, despite several years of successful programs, there are still doubts about its importance. Despite the evidence, many nutrition colleagues are not convinced that food fortification works, and they continue promoting other micronutrient interventions when they are not necessary. I can list the following challenges:

-

Accept that LSFF does not promote the consumption of the food vehicles that are used to deliver the micronutrients. The high intake of all these food vehicles: salt, sugar, oil, refined flours, and even rice is undesirable. However, through fortification, we can promote messages of mode

rating and reducing the intake of fortification vehicles to prevent non-communicable diseases while making sure that people get the nutrients they need. These two goals are compatible. -

Simplify quality control and enforcement practices. It is not necessary to analyze thousands of samples of fortified foods when the monitoring can be easily done based on mass balance methods of the use of fortificants and the amount of fortified food that is being produced, and then to confirm the quality of fortification based on a few composite samples.

-

Recognize that the household level is not the best place to check compliance with fortification standards. Instead, it is important to identify the presence of fortified foods and estimate how much they are contributing to increase micronutrient intake. It has been an error to judge the quality of food fortification programs on the proportion of food samples that comply with the fortification standards at households, use single samples, and employ erroneous analytical methods that do not align with food chemistry principles.

-

Promote local leadership and expertise rather than exporting ideas and concepts based on good intentions that ignore the specific conditions, production, and trade practices of each context and country. LSFF is low cost if based on experience and in the hand of the local stakeholders but not if supported by external advisors and consultants.

FFI: If you were not working in nutrition, what do you think you would be doing?

Dary: This is an interesting question. I have really enjoyed working in nutrition. I did not plan to do this. I prepared myself for being a professional in biochemistry, metabolism, and population genetics. However, I learned that my professional preferences have helped me to contribute to public health nutrition because I bring new insights and experiences that are different from many of my colleagues. Over the years, the attention to metabolism has been weakened, but now we need to reconceptualize our work because we have learned that genetics and physiology need to be considered as diets are only the simplest external factor of nutrition; there are many other factors that we are neglecting.

FFI: Is there anything else you would like to share?

Dary: I would like to thank FFI for the opportunity to share these ideas and for having recognized the wonderful legacy of my colleague, Tim Quick, in public health nutrition. He was a professional in basic science with application to animal nutrition He applied this knowledge to human nutrition, and he knew how the principles of cost efficiency and cost effectiveness that are applied to animal nutrition can also be useful in human nutrition. Our experiences demonstrate that we need to “think outside of the box” for progressing in public health, as well as to illustrate that nutrition requires involvement of all sectors of a society.

This interview is part of the #FFI20 Champions campaign, a celebration of fortification heroes who have helped build a smarter, stronger, and healthier world by strengthening fortification programs over the past 20 years. To read interviews with other champions, visit the #FFI20 Champions campaign homepage.